Anesthesia Considerations for Pediatric Cardiac Catheterization

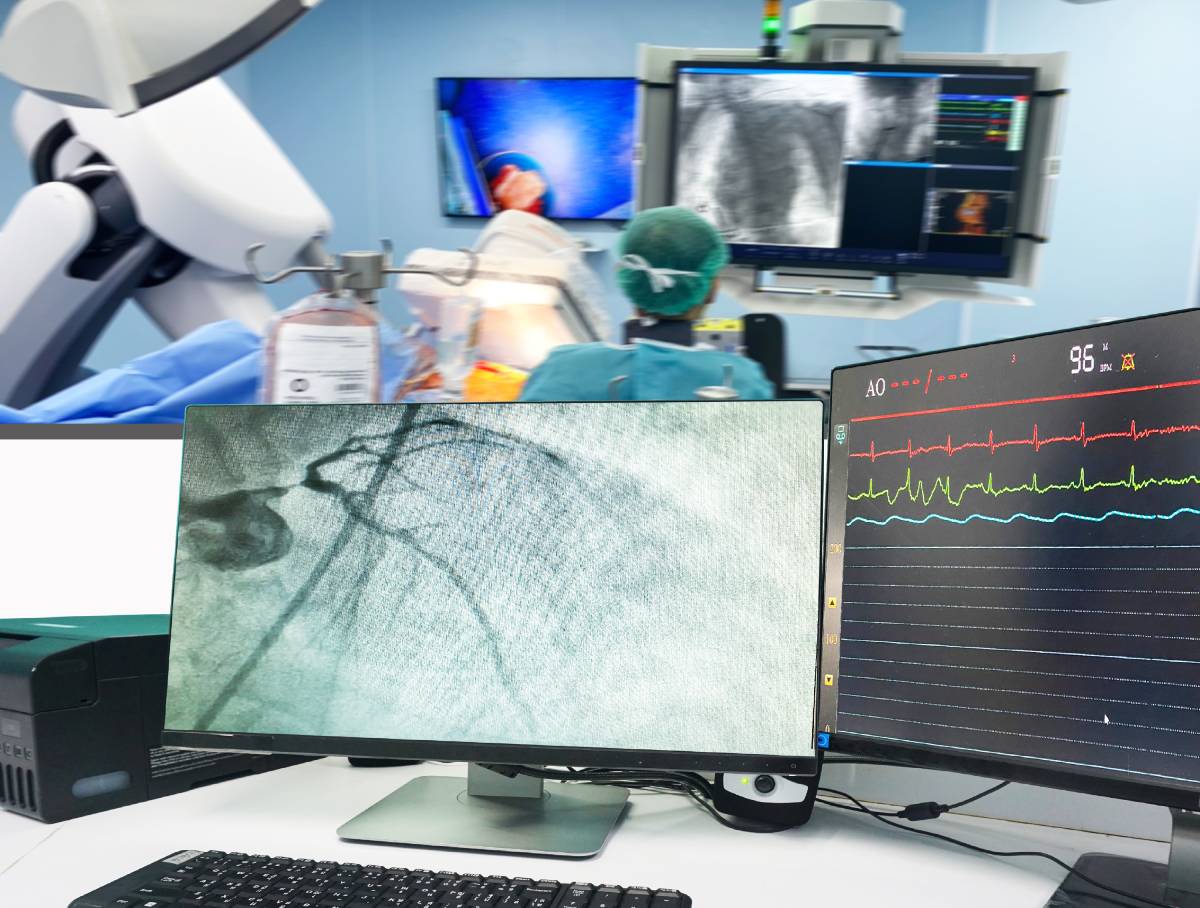

In the past two decades, novel imaging and catheterization technologies have greatly expanded the use of cardiac catheterization in children with heart defects. What was once largely a diagnostic technique is now being used as a therapeutic intervention that can delay or eliminate the need to perform open heart surgery. Catheterization is often used to repair defects in the heart valves or septum, while procedures on vessels commonly include stenting, pulmonary artery balloon angioplasty, and closure of a patent ductus arteriosus. With the increased use of cardiac catheterization in children, efforts have been made to define, stratify, and mitigate the risks pediatric patients face, with significant attention paid to anesthesia considerations and best practices.1

The North American Pediatric Perioperative Cardiac Arrest (POCA) registry, collecting data from 1994-2005, found that 17 percent cardiac arrests in children with heart disease occur in the cardiac catheterization laboratory.2 Overall mortality in the pediatric cardiac catheterization laboratory remains low, with reported death rates between 0.2% and 0.29%. Rates of major adverse events have been reported at 7.2%.3 Unsurprising, higher procedural risk is associated with higher risk of life-threatening events in the catheterization lab.4

Certain conditions, such as pulmonary hypertension, place patients at significant risk, as do demographic categories such as is young age.3 The American Heart Association’s “Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation” Registry, analyzing multicenter data from 2005 to 2016, found that of 203 pediatric cardiac arrests in the cardiac catheterization laboratory reported during this time, 58 percent occurred in patients under one year of age.4

It is difficult to determine to what extent anesthetics contribute to the occurrence of adverse events. One study from China, reviewing 25 articles, found anesthesia-related complications occurred in 7.41% of pediatric patients with congenital heart abnormalities undergoing cardiac catheterization. Complications included dysphoria, respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting, cough, increased respiratory secretion, and airway obstruction.5

Anesthesiologists should be aware of which patients may be at most risk and plan their protocols accordingly. For example, the likelihood of cardiac arrest, pulmonary hypertension crisis, and death is greatest in the catheterization lab in patients with pulmonary hypertension. There are many hazards involved in catheterizing pulmonary hypertension patients, but the procedure is often diagnostically or therapeutically necessary, and there is no evidence that a particular anesthetic protocol is optimal.1

Across patients with a variety of indications, including pulmonary hypertension, either sedation or general anesthesia can be used. Cardiologists and care teams must be aware of the risks associated with each method.3 While sedation provides cardiovascular stability, it is difficult to correctly balance optimal sedation levels, and patients can develop hypoventilation, hypercapnia (increased carbon dioxide in the blood stream), and increased pulmonary vascular resistance. General anesthesia is preferable for most patients, but the hemodynamic effects they exert (including vasodilation, decreased systemic vascular resistance, and myocardial depression) are significant, and pose potential hazards for young children being treated for heart defects.1

There is no ideal anesthetic for pediatric cardiac catheterization, though a variety of anesthesia agents have been used safely. Several studies have shown that propofol is safe and effective in pediatric cardiac catheterization, with a more rapid recovery than other anesthesia agents. Respiratory depression is a risk with propofol, and patients with certain conditions, like aortic stenosis, pulmonary hypertension, or compromised ventricular function should be monitored for hypercapnia. Ketamine has been used in conjunction with propofol with good results, despite concerns of increased pulmonary vascular resistance.1

Thus, a thorough understanding of a patient’s anatomy, physiology, and corresponding perioperative risks is essential in managing a procedure. With increased use of cardiac catheterization in children, risk scores such as the Catheterization Risk Score for Pediatrics (CRISP) have become available to assess a patient’s risk of adverse events.3 When a team briefing and comprehensive assessments of a procedure take place, procedures are more successful: as one study has shown, use of a World Health Organization-derived safe procedure checklist in the cardiac catheterization lab correlated with fewer complications and faster turnarounds, with the benefit of decreased radiation exposure for patients, as well as improved clinician experiences.6

References

- Lam JE, Lin EP, Alexy R, Aronson LA. Anesthesia and the pediatric cardiac catheterization suite: a review. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015;25(2):127-134. doi:10.1111/pan.12551

- Ramamoorthy C, Haberkern CM, Bhananker SM, et al. Anesthesia-related cardiac arrest in children with heart disease: Data from the pediatric perioperative cardiac arrest (POCA) registry. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(5):1376-1382. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181c9f927

- Tierney N, Kenny D, Greaney D. Anaesthesia for the paediatric patient in the cardiac catheterisation laboratory. BJA Educ. 2022;22(2):60-66. doi:10.1016/j.bjae.2021.09.003

- Lasa JJ, Alali A, Minard CG, et al. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in the pediatric cardiac catheterization laboratory: A report from the American Heart Association’s Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation registry: A report from the American heart association’s get with the guidelines-resuscitation registry. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(11):1040-1047. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000002038

- Xie CM, Yao YT. Anesthesia management for pediatrics with congenital heart diseases who undergo cardiac catheterization in China. J Interv Cardiol. 2021;2021:8861461. doi:10.1155/2021/8861461

- Lindsay AC, Bishop J, Harron K, Davies S, Haxby E. Use of a safe procedure checklist in the cardiac catheterisation laboratory. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(3):e000074. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000074